“You know, you're not just an economic actor, you're a citizen, you're a person. You're a human being. You’re an end in yourself, not a means to some other, or someone else’s, end.” - Calum Nicholson

The following series was created to better illustrate different views regarding higher education, to look at it’s past, present and future through the lenses of highly appraised scholars.

In the first instalment of the series, I had the opportunity to interview Calum Nicholson, the director of MCC’s Climate Institute. He holds an undergraduate degree in Social Anthropology from the University of Cambridge, a Masters in Migration Studies from the University of Oxford, and a PhD in Human Geography.

***

The first time I ever heard Calum speak was about a year ago, during an academy held by MCC. He held his lecture on “climate migration”. I was instantly captivated by his way of thinking and reasoning. I’d never heard a similar perspective on climate change and adaptation. It was refreshing.

As the months passed, I was able to attend several other events where Calum was either lecturing, or one of several panellists, and talking about issues as varied as foreign policy, the role of intellectuals in society, and energy cooperation between Hungary and Korea

For a long time, I couldn’t make sense of it. Why do I always find this man outside of the box that I placed him in? Soon enough I realised, there isn’t a box big enough.

But is there one big enough for any of us?

After I had enough dots to connect, I came to the conclusion that Calum is sought after in academic circles not because of his answers but rather his questions.

I definitely have my topics where I'm a “proper” expert. But the truth is, whenever I teach on anything, I try and teach in a way where there's two levels to it. On the one hand, there's the content of what we're talking about, but the truth is students may not be that interested in the topic of climate or migration.

So, I always think “how can I present my work in such a way so that there's something of value in it for all the students, regardless of their interests?” Even if you're not interested in the subject matter that I’m talking about, I'm typically giving it only as an example to illustrate a broader point. I might, for instance, use ’climate migration’ a case study to illustrate a way of thinking about problems in the world, and the problems with how we conceptualise our problems to begin with.

And so, the reason I can talk on a range of topics is because it's not really about being a subject specialist. It's about asking the right questions, in the right order. I usually use a given topic to try and draw attention to a way of looking at problems more generally, which you might then be able to apply to other problems, superficially unrelated to the one we’ve been discussing. One of the reasons I like giving different talks to the same audience is that eventually students start to pick up this way of thinking – of finding the general pattern across a range of particular cases.

"The fact is that there is an image."

But whether it's a duck or rabbit is down to how you interpret it. This the question of what we do with the facts, how we act on and with them, is quite subjective. Arguments can be made either way.

The problem we're having today is I think we're we're becoming a culture that's increasingly obsessive about the factual technical detail and we're losing that sense of the whole into which it fits. And the whole isn’t about facts. It’s about interpretation of facts. Ducks and rabbits. That isn’t a fault, but a feature, of being human.

Can you get by without ever answering?

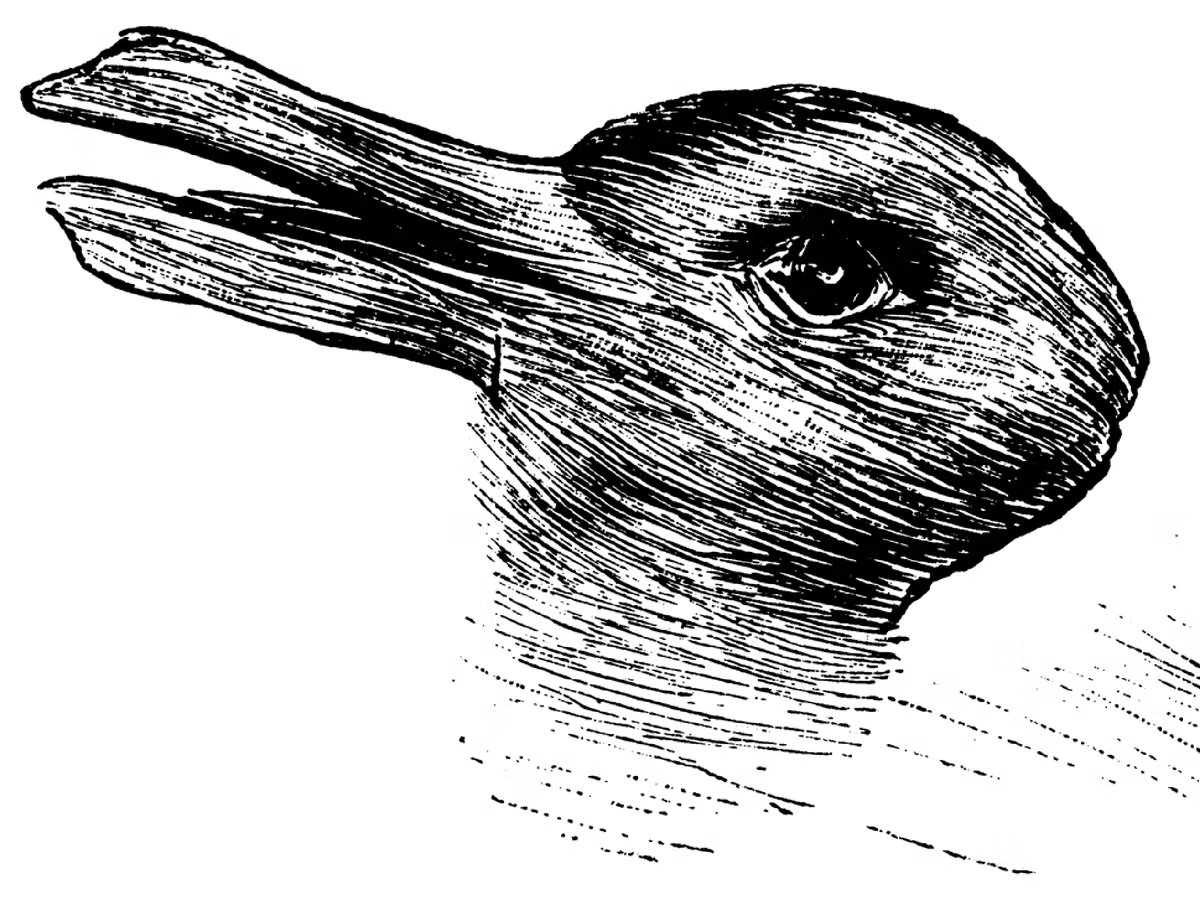

Well, there's a difference between a fact and an answer…. it's not that I'm not giving an answer to avoid taking a position – that’s not the point. My point is that there are almost always two ways of looking at a fact. This is best illustrated with the famous image of the ‘duck/rabbit’:

The fact is that there is an image. But whether it's a duck or rabbit is down to how you interpret it. This the question of what we do with the facts, how we act on and with them, is quite subjective. Arguments can be made either way.

The problem we're having today is I think we're we're becoming a culture that's increasingly obsessive about the factual technical detail and we're losing that sense of the whole into which it fits. And the whole isn’t about facts. It’s about interpretation of facts. Ducks and rabbits. That isn’t a fault, but a feature, of being human.

Do you think that we can teach generalists on the same scale that we teach specialists nowadays with the same model, university or higher education?

’So it used to be that you went to university to be developed as a person. It was an end in itself…meaning you were an end in yourself -not just an economic actor, but a citizen, a person, a human being.

’But these days, it's tricky because what has happened in the last 40 years is that universities in general have started to be run on a neoliberal technocratic model. We only prize technical skills, or narrow forms of ’expertise’. We have lost sight of the value of the generalist.I think we have a general problem in society now of having a culture that is not conducive to teaching people how to think in a general sense, nor to incentivize them to do it because most people are incentivized just to watch their own small patch.

***

Calum is an advocate for seeing the whole. He thinks it’s important to question our assumptions. He realises that an individual also contains a plurality of perspectives, not all of which are reconcilable, and that this isn’t a fault, but an irreducible feature, of being human. Our institutions, particularly educational ones, should work to accommodate this very human impulse, rather than suppress it.

When choosing a Ba, Masters or Phd Course, even when deciding on majors and minors students are faced with a decision. Round themselves or sharpen their edges? Nowadays, with heavy government support for highly specialised disciplines, the number of students choosing the latter are high as ever. In a world where a career is a hassle, and not a privilege for most, we most reconsider if we want to further distance ourselves from the principle these institutions where founded on: The love and thirst for all knowledge.